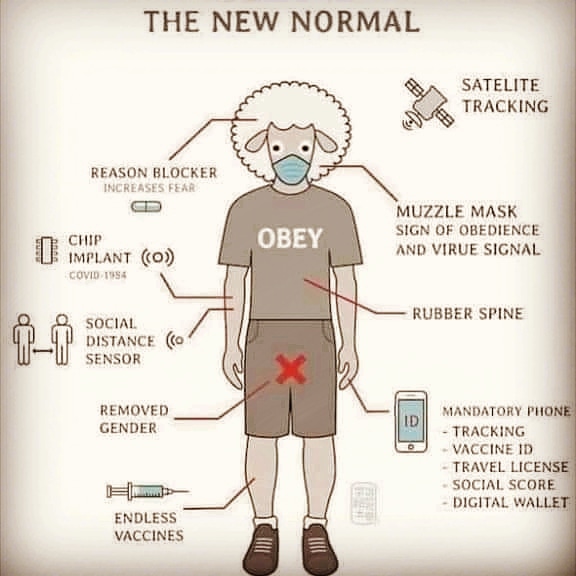

It ain’t a conspiracy theory if’n it’s true…

For the first time, the innovative CRISPR gene editing method has been used on squid, marking a milestone in the scientific study of these creatures – and opening up many new areas of potential research.

CRISPR enables very precise, speedy, and low-cost DNA edits. Put simple, the ingenious molecular workings of the method are often described as something that allows us to ‘cut’ and ‘paste’ genes; in humans it promises to give us a way of tackling disease and killing superbugs at the genetic level.

In this case CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing was used on Doryteuthis pealeii (the longfin inshore squid) to disable a pigmentation gene, turning off the pigmentation usually found in the squid eye and inside specialised skin cells called chromatophores.

“This is a critical first step toward the ability to knock out – and knock in – genes in cephalopods to address a host of biological questions,” says marine biologist Joshua Rosenthal, from the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) at the University of Chicago.

As students, parents, and schools prepare the new school year, universities are considering ways to make returning to campus safer. Some are considering and even mandating that students install COVID-related technology on their personal devices, but this is the wrong call. Exposure notification apps, quarantine enforcement programs, and similar new technologies are untested and unproven, and mandating them risks exacerbating existing inequalities in access to technology and education. Schools must remove any such mandates from student agreements or commitments, and further should pledge not to mandate installation of any technology.

Even worse, many schools—including Indiana University, UMass Amherst, and University of New Hampshire—are requiring students to make a general blanket commitment to installing an unspecified tracking app of the university’s choosing in the future. This gives students no opportunity to assess or engage with the privacy practices or other characteristics of this technology. This is important because not all COVID exposure notification and contact tracing apps, for example, are the same. For instance, Utah’s Healthy Together app until recently collected not only Bluetooth proximity data but also GPS location data, an unnecessary privacy intrusion that was later rolled back. Google and Apple’s framework for exposure notification based on Bluetooth is more privacy-protective than a GPS-based solution, but the decision to install it or any other app must still be in the hands of the individuals affected.

It’s 2022 and you’ve just arrived at the travel destination of your dreams. As you get off the plane, a robot greets you with a red laser beam that remotely takes your temperature. You’re still half asleep after a long transoceanic flight, so your brain barely registers the robot’s complacent beep. You had just passed similar checks when boarding the plane hours ago so you have nothing to worry about and can just stroll to the next health checkpoint.

As you join the respiratory inspection queue, a worker hands you a small breathalyser capsule with a tiny chip inside. Conceptually, the test is similar to those measuring drivers’ alcohol levels, but this one detects the coronavirus particles in people’s breath, spotting the asymptomatic carriers who aren’t sick but can infect others. By now you know the drill, so you diligently cough into the capsule and drop it into the machine resembling a massive microwave. You wait for about 30 seconds and the machine lights up green, chiming softly. You may now proceed to immigration, so you fumble for your passport and walk on.

These technologies may sound like science fiction, yet they are anything but. If you had travelled earlier this year when countries began locking down, you may have already spotted the remote infrared thermometers used in airports. However, while thermometers are helpful, they aren’t ideal. People can have fevers for others reasons or may harbour coronavirus without symptoms. To spot early infections or asymptomatic carriers, one has to check for the coronavirus particles in their breath.

That’s where the breathalyser comes in. You haven’t yet seen it at transit hubs, but it already exists at the photonics lab of Gabby Sarusi, professor at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel. When Covid-19 struck and hospitals worldwide struggled to build fast and accurate biological diagnostic tests, Sarusi looked at the problem differently. As a physicist, he viewed the coronavirus’ spiky sphere not as a biological agent but as a nano-sized particle that can be sensed by specialised electrical equipment. When tossed into the midst of an electromagnetic field, the particles cause certain “interference” to the flow of electromagnetic waves, which can be detected. That’s what happens when the capsule is dropped into the microwave-resembling machine.

“We are taking the chip inside the capsule and we’re measuring it with a spectrometer that’s radiated with the magnetic waves,” Sarusi explained. If coronavirus particles are present, he said, “we can sense the shift.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.