In the closing days of 2025, the White House turned an opioid crisis into a national security drama. Standing in the Oval Office during a Mexican Border Defense Medal ceremony on December 15, President Donald Trump declared that he would sign an executive order to classify fentanyl as a “weapon of mass destruction,” calling the announcement “historic.” Treating a synthetic painkiller like a nuclear bomb says more about Washington’s mindset than about the drug. Though drug overdose deaths declined in 2024, 80,391 people still died and 54,743 of those deaths were from opioids. Those numbers mark a public‑health emergency. Rather than tackle fentanyl abuse as a medical or social problem, the administration reframed it as an existential threat requiring military tools. Labeling a narcotic a WMD creates a pretext for war and sidesteps due process. This move grows out of a political culture that uses fear of invisible enemies—terrorists, microbes, drugs—to justify extraordinary power.

Past and present administrations have blurred the line between law enforcement and warfare. Since September 2025 the United States has launched more than twenty strikes on boats in the Caribbean and Pacific suspected of carrying narcotics, killing over eighty people. Experts note that little proof has been made public that the vessels contained drugs or that blowing them out of the water was necessary. Yet the assaults continued, and on December 10 the U.S. Navy seized a sanctioned Venezuelan oil tanker off Venezuela’s coast, sending oil prices higher. Trump boasted it was the largest tanker ever seized and said, when asked about the cargo, “We keep it, I guess.” Caracas denounced the action as “blatant theft.” The administration justified the operation as part of its anti‑drug campaign, but the target was not an unmarked speedboat; it was a carrier of crude oil, the sanctioned state’s main revenue source. Calling fentanyl a WMD makes such seizures look like acts of defense and blurs war and policing.

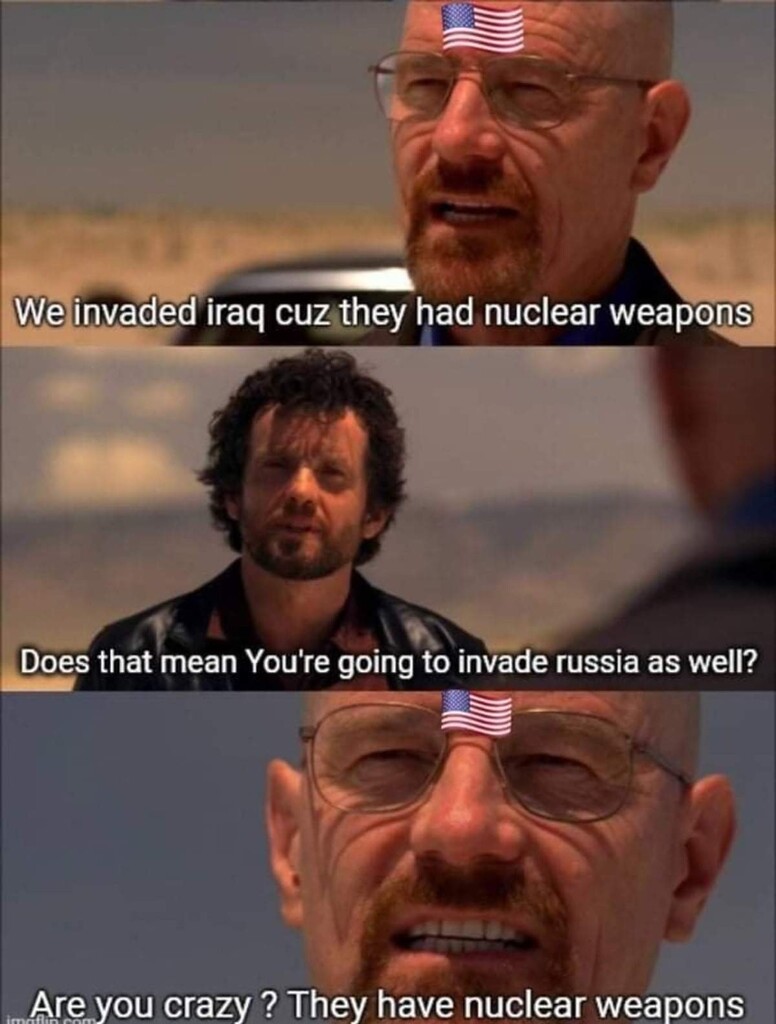

For students of recent history, this conflation of domestic threats with existential danger is hauntingly familiar. After September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush and his advisers claimed Iraq was developing anthrax, nerve gas and nuclear weapons. Vice President Dick Cheney insisted there was “no doubt” Saddam Hussein possessed WMD and was amassing them for use against America and its allies. Those arguments resonated with a populace still traumatized by the attacks. Fear allowed hawks to portray preemptive war as the only way to prevent a “mushroom cloud,” and in March 2003 the United States invaded Iraq. Investigations later found no factual basis for the claims that Iraq possessed WMD or collaborated with al‑Qaida. The smoking gun was a phantom, but by the time the truth emerged, Baghdad had been captured and the region destabilized for a generation.

One of the most tragic figures in that saga was Secretary of State Colin Powell. On February 5, 2003, he sat before the United Nations Security Council holding a glass vial he said could contain anthrax. He described Iraq’s alleged weapons labs and insisted the case was based on “solid intelligence.” The performance helped clinch support for war. Years later it became clear the intelligence was false and cherry‑picked, and no WMD were found. Powell later admitted the presentation was wrong and had blotted his record. Using a decorated officer’s credibility to sell a war built on falsehoods shows how propaganda can override reason.

The consequences of the Iraq War were catastrophic. The Defense Department records 4,418 U.S. service members dead in Operation Iraqi Freedom, including 3,481 killed in hostile action. Brown University’s Costs of War Project estimates that the post‑9/11 wars have cost the United States around $8 trillion and killed more than 900,000 people. About $2.1 trillion of that went to the Iraq/Syria theater. These figures exclude indirect deaths and future costs for veterans’ care. Millions of Iraqis were killed, injured or displaced, fueling sectarian violence and extremism. The war enriched defense contractors and expanded the military‑industrial complex while leaving ordinary people to pay the bill.

You must be logged in to post a comment.