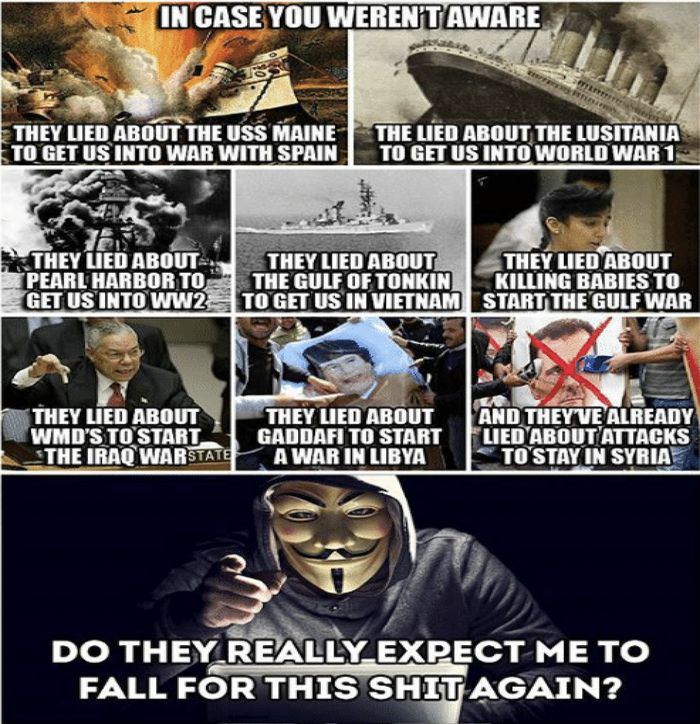

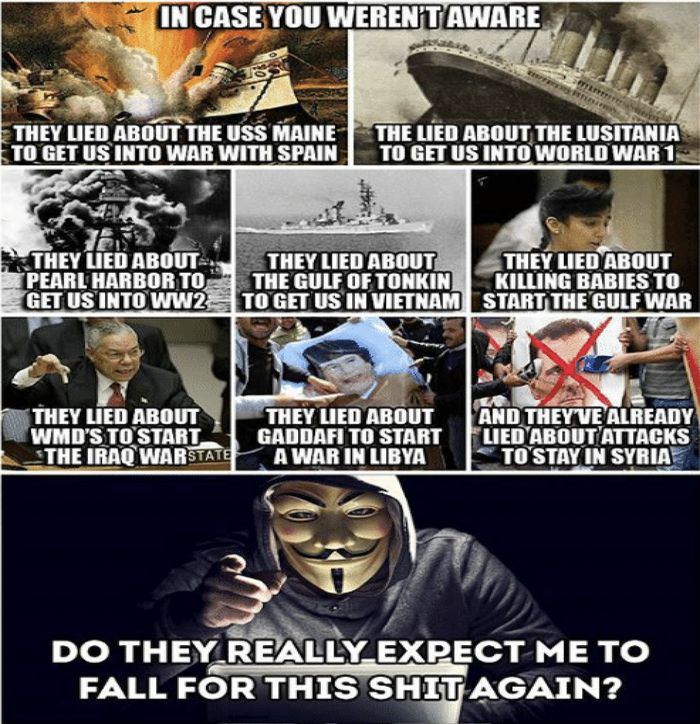

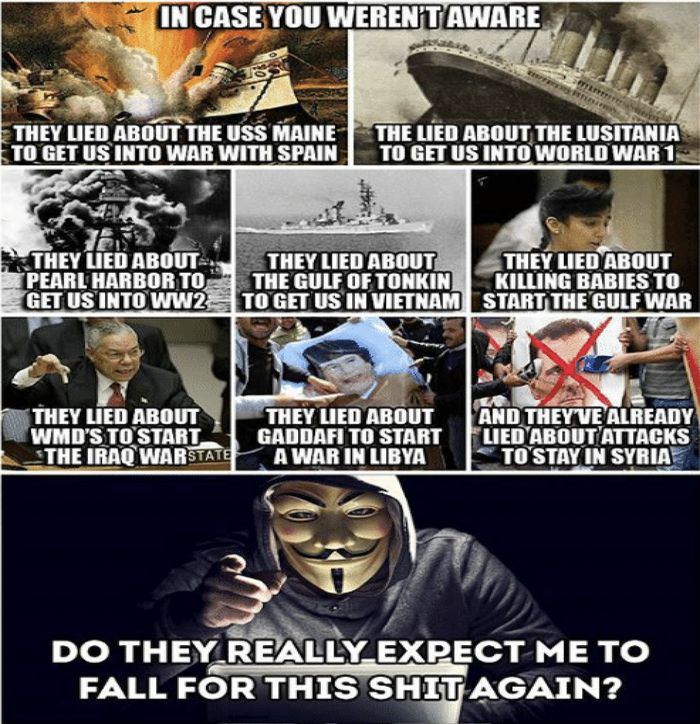

I’m sure they’re being straight with us this time…

In one of the more shocking episodes of the Cold War tens of thousands of Nazi war criminals and their fascist allies were smuggled out of Europe and resettled around the world in places like Argentina, Canada, Australia and the United States. Others were resettled throughout the middle east a few ended up as far away as South East Asia. They were considered too valuable by western intelligence to face justice for their crimes. 27 Million people were killed in the Soviet Union alone, 4 million in Poland, I’ve written of the many uses these fascist exiles were put to in my previous articles. They were used as spies, propagandists and terrorists in the west’s secret war on the Soviet Bloc and even non-aligned countries like Yugoslavia. They went to work for Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty, universities, and think tanks and were even used to turn out the vote for the Republican Party in the US. The Ukrainian fascists formed a powerful lobby in the US, Canada and Australia. In Canada for example the Ukrainian Nazi exiles are so powerful that they have placed one of their own at the head of Canada’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs Chrystia Freeland. As the cold war neared it’s end these fascist movements in exile returned home seizing power with the help of Western Intelligence in Croatia, Bosnia, Kosovo, in the 1990’s and Ukraine in 2004 and again in 2014. They also have a great deal of influence in the Baltic countries of Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania where SS veterans hold yearly parades and are treated as heroes. Thus the fascist exiles have gone from a scandalous chapter in cold war history to the cause of a new cold war with Russia. They have played a vital role in the increasing danger of fascism worldwide.

Students of CIA or MI6 history won’t be surprised to see them conspiring with Nazis and Fascists. The CIA has been involved in countless fascist coups from Guatemala in 1954 to Ukraine in 2014. CIA architect Allen Dulles was notorious for his nazi business ties before and during the war. The ratlines were only one element of CIA involvement with the nazis which included, Operation Sunrise (Dulles separate peace with the SS near wars end,) the recruitment of Reinhard Gehlen and his Org of nazi war criminals, the phony denazification of West Germany, Operation Bloodstone (placing nazis in american universities and think tanks), Operation Paperclip (recruiting Nazi Scientists) , the Free Europe Committees, fascist stay behind networks like GLADIO, and more. The British did not even wait for World War 2 to end before siding with Greek Fascists in crushing the Greek Partisans who had single handedly defeated the Nazi occupation of their country. MI6 played a key role in using the fascist exiles to wage war on the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia between the disbanding of OSS in 1945 and the creation of the CIA in 1947. MI6 had worked with these same fascists before the war when the Ustashi and Stepan Bandera’s OUN Ukrainian fascists were both on their payroll. CIA architect Allen Dulles and his brother John Foster had like the british been in business with the fascists before during and after the war.

More shocking is the role of the Vatican in all this. Perhaps it shouldn’t be so surprising given the history of the Church. During the Middle ages clergy often played the role of diplomats, spies and technocrats in royal courts as they were comparatively well educated and often of noble lineage. In Italy the Vatican held vast territories and became a state pursuing it’s own ruthless realpolitik waging wars for territory. Popes like the Borgias became notorious for their ruthlessness and corruption. The church also became a vast business enterprise holding valuable lands, manufacturing goods, and eventually making a fortune in the slave trade. They would play a key role in the conquest of the Americas and the genocide that followed and would compete with the protestant missionaries in the conquest of Asia and Africa. The chance to seize the vast assets the church accumulated over the centuries became a driving force behind the Reformation and the bloody wars of religion that lasted centuries. Then came the French Revolution and democracy became a major threat to the wealth of the church. Worse it unleashed revolutions across Europe including Italy and the church lost most of it’s territory. The Vatican became as obsessed with battling revolution as it had once been with battling heresy. Then came World War 1 and the Russian Revolution which threatened to spread across Europe. If the church was terrified of liberal democracy you can imagine it’s horror at the triumph of “godless Communism.” To sum things up the Vatican had millennia of experience in espionage, propaganda, diplomacy setting up NGOs as fronts and other instruments of soft power and had been fighting for centuries to preserve it’s power and it’s vast fortune. It isn’t my intent to single out the Catholic Church as one could also write a book on Orthodox or protestant ties to fascism. Less well known are the Buddhist, Hindu or Muslim ties to fascism. American evangelicals for example have long played an important role in international fascist networks like WACL.

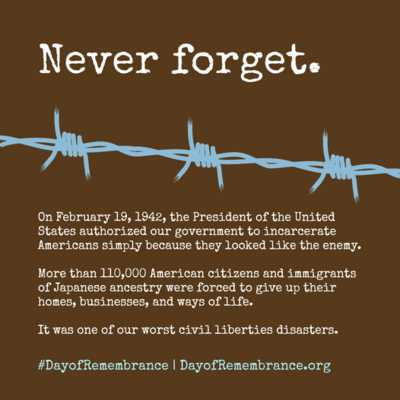

This is the last installment in a series on the nadir, or low point, of the U.S. Supreme Court. This was the period from 1937 to 1944, when the court stopped protecting the Constitution’s limits on the federal government. Our Constitution has never fully recovered.

The first, second, third, fourth, fifth and sixth installments related to how the justices initially tried to balance the demands of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal with the Constitution’s rules. In 1937, however, Roosevelt began to replace sitting justices with New Deal enthusiasts who had no prior judicial credentials. The remodeled bench successively discarded limits on federal spending, federal property ownership, and federal economic regulation. In at least one case, it abandoned habeas corpus and the right to a trial by jury.

This final installment addresses the court’s role in what was, aside from slavery, the most egregious violation of civil rights in U.S. history. It adds some observations on how the court’s abysmal record from 1937 to 1944 continues to affect us today.

Prescott Bush was a partner of Brown Brothers Harriman & Co and director of Union Banking Corporation which had close relations with German corporate interests including Thyssen Steel, a major company involved in the Third Reich’s weapons industry.

“…[N]ew documents, declassified [in 2003], show that even after America had entered the war [December 8, 1941] and when there was already significant information about the Nazis’ plans and policies, he [Prescott Bush] worked for and profited from companies closely involved with the very German businesses that financed Hitler’s rise to power. It has also been suggested that the money he made from these dealings helped to establish the Bush family fortune and set up its political dynasty” (The Guardian, September 25, 2004)

.****

Without US support to Nazi Germany, the Third Reich would not have been able to wage war on the Soviet Union. Germany’s oil production was insufficient to wage a major military campaign. Throughout the war, the Third Reich relied on regular shipments of crude oil from US Standard Oil owned by the Rockefeller family.

The main producing countries in the early 1940s were: the United States (50% of global oil production), the Soviet Union, Venezuela, Iran, Indonesia, and Romania.

Without a steady supply of oil, Germany would not have been able to conduct Operation Barbarossa which was launched on June 22, 1941. The invasion of the Soviet Union was intent upon reaching and taking control of the oil resources of the Soviet Union in the Caucasus and Caspian sea regions: the oil of Baku.

In the early 1930s, there was a concerted effort on the part of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party to consolidate power. The back end methods of this consolidation are well taught and well known, fear, intimidation, and street violence. However, the front part, the legitimate part, is less studied by the majority of the public.

Knowing that his radical Nazi party was in a precarious position electorally, Hitler set out to bring centrist parties into the fold. One such party was the Centre Party which had long been a bastion for political German Catholics. Hitler aimed to reduce the political power of the Catholic Church while receiving an international agreement with the Holy See. He achieved both brilliantly.

On their faces, it does not seem like the Pope and the Nazis would have much in common, and in many cases, they did not. There was one binding similarity between the two that brought them close together in the early 1930s: hatred for communism.

Both the new Nazi government in Germany as well as the Vatican in Italy were both publicly and diametrically opposed to communism. The Nazis were opposed to it for political reasons while the Catholics were opposed for religious reasons. Communism was a completely atheist system which had cracked down on Christianity in Russia and elsewhere leading to alarm in Vatican City.

(As a side note, the Papacy would remain staunchly anti-communist all the way through the Cold War.)

In 1933, Pius XI and one of his top advisors, Eugenio Pacelli who would succeed Pius XI as Pius XII, signed the Reichskonkordat with Germany. This sweeping document paved the way for Hitler to sweep the Catholic influence in Germany aside while giving him an international political victory on the world stage.

A six-year cold case investigation into the betrayal of Anne Frank has identified a surprising suspect in the mystery of how the Nazis found the hiding place of the famous diarist in 1944.

Anne and seven other Jews were discovered by the Nazis on Aug. 4 of that year, after they had hid for nearly two years in a secret annex above a canal-side warehouse in Amsterdam. All were deported and Anne died in the Bergen Belsen camp at age 15.

A team that included retired U.S. FBI agent Vincent Pankoke and around 20 historians, criminologists and data specialists identified a relatively unknown figure, Jewish notary Arnold van den Bergh, as a leading suspect in revealing the hideout.

Some other experts emphasised that the evidence against him was not conclusive.

Investigating team member Pieter van Twisk said the crucial piece of new evidence was an unsigned note to Anne’s father Otto found in an old post-war investigation dossier, specifically naming Van den Bergh and alleging he passed on the information.

The note said Van den Bergh had access to addresses where Jews were hiding as a member of Amsterdam’s wartime Jewish Council and had passed lists of such addresses to the Nazis to save his own family.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Japanese planes, launched from aircraft carriers, attacked the American fleet at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, sinking or heavily damaging 18 ships (including eight battleships), destroying 188 planes, and leaving over 2,000 servicemen killed.

The next day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt denounced this “day of infamy” before Congress, from whom he secured an avid declaration of war.

Up until then, however, Americans had overwhelmingly opposed involvement in World War II. They had been thoroughly disillusioned by the First World War:

When the Maine sank, the proactive Assistant Secretary of the Navy had been Teddy Roosevelt. After the 1898 Spanish-American War he became governor of New York, and by 1901 was President of the United States. When the Lusitania sank, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy was his distant cousin Franklin D. Roosevelt – who likewise went on to become governor of New York and then President.

Just as coincident: during the Lusitania affair, the head of the British Admiralty was yet another cousin of Franklin D. – Winston Churchill. And in a chilling déjà vu, as Pearl Harbor approached, these two men were now heads of their respective states.

You must be logged in to post a comment.