They didn’t read it at all…

When I first came to Washington in 1995 as a CBS News correspondent, the U.S. Capitol building was truly “The People’s House.” Anybody could walk in and browse around, walk the historic marble floors, look at the historic statues. No metal detectors. No police or security guards removing perfume from your purse in case it’s a plot to build an explosive device from liquid.

The same sort of access was available to the public and press at most federal buildings at the time.

Even the White House, more secure than the other buildings back then, was less like a command bunker. Anybody could drive right along the public street adjacent to the back of the White House and take a look.

Of course everything, understandably, changed with the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Most any building occupied by the federal government became a fortress. Concrete barriers were erected all over the city to make it harder for a car bomber to drive into a building. Police are routinely stationed on streets, at places they rarely were seen before. Metal detectors, police and security guards, sweeps with mirrors under your car as you enter a parking garage, all became the norm.

A complete web of rules and restrictions was adopted, dictating who could enter what building and when. It involved various combinations of: Call ahead. Get clearance. Submit your Social Security number. Show your driver’s license. Have an escort.

And that street by the White House was closed to ordinary vehicle traffic. It’s been treated to an expanding array of fencing, guard shacks and Secret Service presence.

Shortly after 9/11, many of us wondered if the changes to our nation’s capital would be permanent — and hoped it would not have to be. Since then, security measures have expanded further. And with each new restriction, there’s opportunity for abuse. Federal officials sometimes use supposed security concerns as an excuse to control access and information; the public becomes further distanced from the elected and hired officials who are supposed to work for them.

Years ago, when I was breaking news about the Obama administration’s “Fast and Furious” scandal, it was nearly impossible for me to get access to then-Attorney General Eric Holder to ask any questions. One day, the Department of Justice (DOJ) hastily announced a briefing about Fast and Furious to be held at its offices. CBS sent me out the door to attend.

As I rushed out the door, Holder’s right-hand press aide, Tracy Schmaler, called to tell me I would not be admitted. Only the friendly beat reporters regularly assigned to DOJ would be allowed in through security.

Clearly, I wasn’t a security concern. They knew me and, besides, I had undergone FBI background checks to get White House hard passes; I was no threat. This was a seminal moment. At the time, I told CBS managers we should challenge the administration’s use of “security concerns” to exert politically motivated control over who enters a public building. I argued that it would only get worse if we allowed federal officials to use a security posture as a way to determine who covers them and who does not. Although the managers agreed, we didn’t pursue the challenge.

Some years ago, after a set of budget cuts, the main public entrance to the Russell Senate Office Building across from the Capitol was temporarily shut down. I wondered if it was part of an effort by sequestration opponents to make it visibly look as if important, tangible things were being cut. After all, the closing of the entrance inconvenienced thousands of people daily visiting and working at the Capitol. Years later? The grand entrance never reopened, as far as I know.

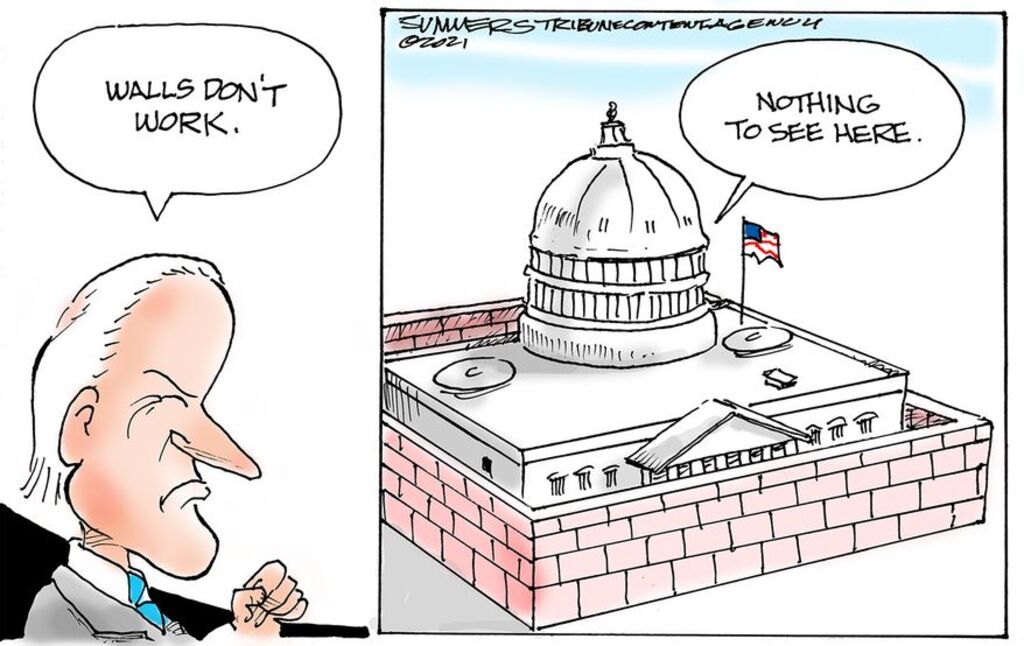

This week, upon my most recent visit to Capitol Hill for work, security was tighter than I’ve ever seen before. Tighter than after 9/11, and tighter than during the presidential inaugurations I’ve covered. Unspecified fears over some sort of upcoming security threat have led to what looks like a militarized zone, with police, National Guard troops, blocked roads and new fencing sporting circles of barbed concertina wire atop. They call the circle around the fortification “The Perimeter.”

“Are you trying to get into The Perimeter?” a military officer asked as my Uber driver pulled up to find out if we could get anywhere close to the congressional offices surrounding the Capitol.

Then, on Thursday, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) demanded more funding for more security, blaming COVID-19 and the Jan. 6 Capitol riot conducted by what she called “all the president’s men.” And the Pentagon said it is reviewing a Capitol Police request to extend the National Guard’s presence for two months beyond the deployment’s scheduled end on March 12. All this on a day when Capitol Hill security was tightened even further because of reports that some members of an unnamed militia group chatted online about trying to breach the Capitol again.

Admittedly, I don’t have access to the intelligence to which they’re responding, and the measures could well be appropriate. But I’ve been to war-torn and third-world nations that didn’t look anything like this. The security measures, to me, looked like enough to fight a large army.

Twitter failed to respond to a letter by Republican Reps. Jim Jordan from Ohio, and Ken Buck from Colorado, who requested documentation and data to aid a Congressional investigation by the House Judiciary Committee. The request was first made in July 2020.

In the letter, the Republican House representatives requested Twitter provide the House Judiciary Committee with documentation and data related to several issues, including the platform’s content moderation policies, its assertion that President Trump’s warnings to protesters violated its policies (last summer Trump warned rioters they would face violence from the National Guard), and its decision to fact check the then-President’s tweets.

In the recent letter, dated March 4, the Republican Reps claim that the request was first sent last July. Twitter did not provide the requested information then, and is yet to respond to the most recent letter.

For the third time in less than five months, the U.S. Congress has summoned the CEOs of social media companies to appear before them, with the explicit intent to pressure and coerce them to censor more content from their platforms. On March 25, the House Energy and Commerce Committee will interrogate Twitter’s Jack Dorsey, Facebooks’s Mark Zuckerberg and Google’s Sundar Pichai at a hearing which the Committee announced will focus “on misinformation and disinformation plaguing online platforms.”

The Committee’s Chair, Rep. Frank Pallone, Jr. (D-NJ), and the two Chairs of the Subcommittees holding the hearings, Mike Doyle (D-PA) and Jan Schakowsky (D-IL), said in a joint statement that the impetus was “falsehoods about the COVID-19 vaccine” and “debunked claims of election fraud.” They argued that “these online platforms have allowed misinformation to spread, intensifying national crises with real-life, grim consequences for public health and safety,” adding: “This hearing will continue the Committee’s work of holding online platforms accountable for the growing rise of misinformation and disinformation.”

House Democrats have made no secret of their ultimate goal with this hearing: to exert control over the content on these online platforms. “Industry self-regulation has failed,” they said, and therefore “we must begin the work of changing incentives driving social media companies to allow and even promote misinformation and disinformation.” In other words, they intend to use state power to influence and coerce these companies to change which content they do and do not allow to be published.

The United States Senate’s Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs saw two videos vaporized in Stalinist fashion because Youtube’s censor didn’t see them as fit for public consumption.

The Wall Street Journal reported on the disturbing, Chinese-level act of censorship, which is raising alarms about where this is all heading:

Google’s YouTube has ratcheted up censorship to a new level by removing two videos from a U.S. Senate committee. They were from a Dec. 8 Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs hearing on early treatment of Covid-19. One was a 30-minute summary; the other was the opening statement of critical-care specialist Pierre Kory.

It is interesting that one of the committee hearings relates directly to cheap drugs that might be used to treat COVID-19.

“At the December hearing, he presented evidence regarding the use of ivermectin, a cheap and widely available drug that treats tropical diseases caused by parasites, for prevention and early treatment of Covid-19,’ the Journal reported. “He described a just-published study from Argentina in which about 800 health-care workers received ivermectin and 400 didn’t. Not one of the 800 contracted Covid-19; 58% of the 400 did.”

Big Tech now seems fully committed to preventing transparency on public policy issues, even to the extent that it would ban videos from the U.S. Senate. That level of brazenness suggests that the corporations feel like they are untouchable. And beyond some lip service to holding these companies responsible, the U.S. government has thus far done nothing to challenge that assessment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.