Once a COVID-19 vaccine is approved for public use, officials around the world will face the monumental challenge of vaccinating billions of people, a logistical operation rife with thorny ethical questions. What if instead of orchestrating complicated and resource-intensive campaigns to vaccinate humans against emerging infectious diseases like COVID-19, we could instead stop the zoonotic diseases that sometimes leap from animals to people at their source? A small, but growing number of scientists think it’s possible to exploit the self-propagating properties of viruses and use them to spread immunity instead of disease. Can we beat viruses like SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus, at their own game?

A virus that confers immunity throughout an animal population as it spreads in the wild could theoretically stop a zoonotic spillover event from happening, snuffing out the spark that could ignite the next pandemic. If the wild rats that host the deadly Lassa virus, for example, are vaccinated, the risks of a future outbreak among humans could be reduced. For at least 20 years, scientists have been experimenting with such self-spreading vaccines, work that continues to this day, and which has gained the attention of the US military.

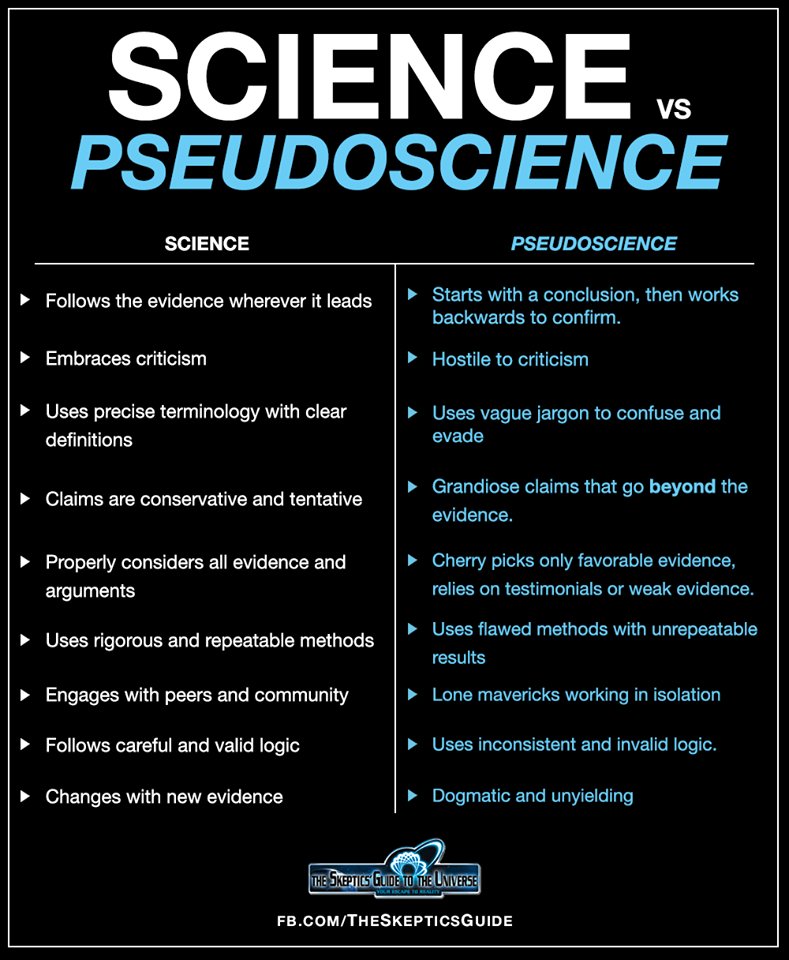

For obvious reasons, public and scientific interest in vaccines is incredibly high, including in self-spreading vaccines, as they could be effective against zoonotic threats. The biologists Scott Nuismer and James Bull generated fresh media attention to self-spreading vaccines over the summer after publishing an article in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution. But the subsequent reporting on the topic gives short shrift to the potentially significant downsides to releasing self-spreading vaccines into the environment.

Self-spreading vaccines could indeed entail serious risks, and the prospect of using them raises challenging questions.

Who decides, for instance, where and when a vaccine should be released? Once released, scientists will no longer be in control of the virus. It could mutate, as viruses naturally do. It may jump species. It will cross borders. There will be unexpected outcomes and unintended consequences. There always are.

While it may turn out to be technically feasible to fight emerging infectious diseases like COVID-19, AIDS, Ebola, and Zika with self-spreading viruses, and while the benefits may be significant, how does one weigh those benefits against what may be even greater risks?

Keep reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.