The McDonald’s stirring spoon was a fixture of the popular fast food chain in the 1970s — a long, plastic utensil with a small scoop on one end and the signature golden arches on the other. It was a simple tool, designed to stir cream and sugar into coffee and nothing more. But that wasn’t all it was used for.

Indeed, the innocent stirring spoon, colloquially called the McSpoon, soon became an unlikely scapegoat in the War on Drugs.

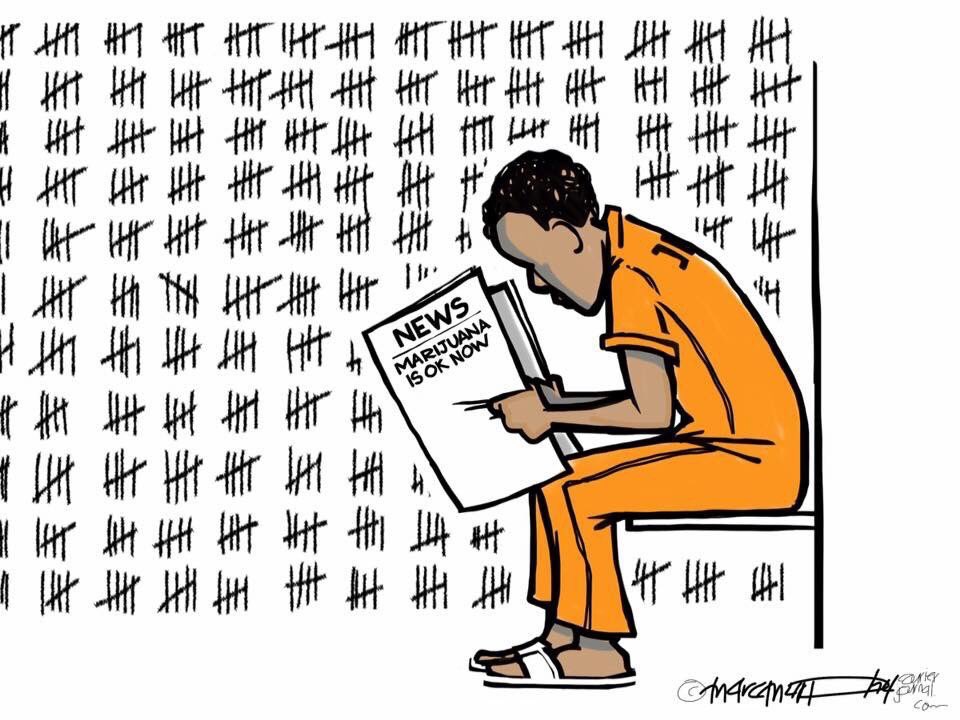

In 1971, Richard Nixon declared the drug epidemic public enemy number one, kicking off the “war on drugs” that’s still being waged today. Despite the creation of the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and efforts to shut down the Colombian drug trade, drug use only spiked in subsequent years. Cocaine use, in particular, was at its peak in those years, with a whopping 11 percent of the adult population using it.

To help curb the problem, anti-drug folks created a big push against the sale and use of drug paraphernalia — pipes, rolling papers, coke spoons and the like — leading to the DEA’s Model Drug Paraphernalia Act in 1979.

The law, adopted by almost every state government, contained a vague definition of paraphernalia that could include just about everything. A silly straw and a plastic sandwich bag could be paraphernalia under the right circumstances.

Angry about the proposed law, one member of the Paraphernalia Trade Association (PTA, representing smoke shop vendors) mocked the law’s vague wording with, that’s right, a McDonald’s stirring spoon.

“This,” he said, “is the best cocaine spoon in town and it’s free with every cup of coffee at McDonalds.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.