Alexis de Tocqueville (1805 – 1859) was a French diplomat, political philosopher and historian, best known for his works ‘Democracy in America’ and ‘The Old Regime and the Revolution’. According to Mani Basharzad, what Tocqueville teaches us was echoed in Sir Roger Scruton, the torchbearer of conservative thought in England in the last century.

Using Tocqueville’s philosophy, Basharzad explains how freedom is lost through the lack of taking personal responsibility.

The Psychology of Freedom

The following is an extract from the article ‘Psychology, Security, and the Subtle Surrender of Freedom’ written by Mani Basharzad and published by The Daily Exonomy. You can read the full article HERE.

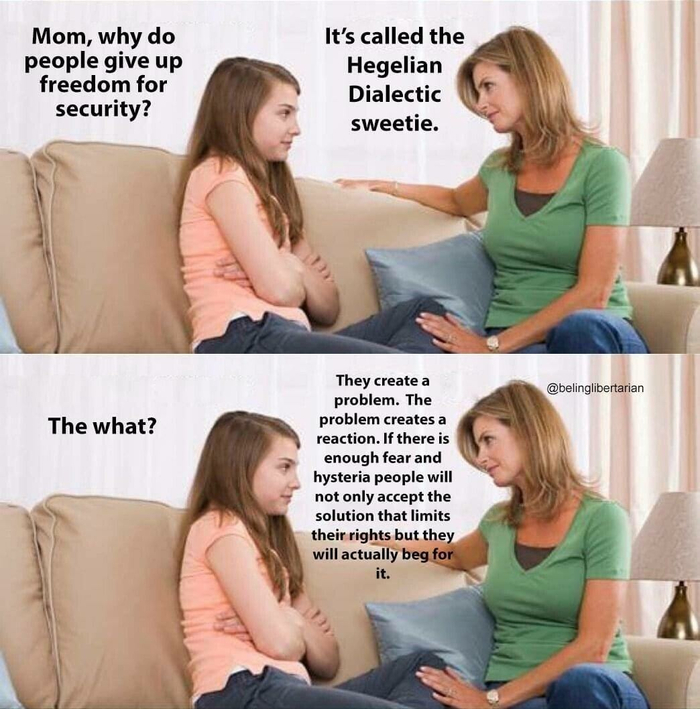

Tocqueville’s special contribution lies in showing us the psychology of freedom. For him, liberty was not only a matter of institutions and individual rights, but also of the deeper attitudes that hold everything together and make freedom work. On this basis, we arrive at one of the most disturbing parts of Tocqueville’s thought: freedom can be lost in democracies through democratic means. It is not only overthrown by revolutions, coups or violent movements; it can disappear in a calm, civil and apparently legitimate way.

The shift of consciousness Tocqueville described is this: people may love freedom, but they do not always love the responsibility that freedom demands. They look for someone else to bear the responsibility that comes with freedom. And what better candidate than government? Do not trouble yourself about the uncertain future; we will decide for you. Do not worry about the consequences of your choices; we will absorb them. We will shield you from danger.All we require is a little more power, a little more of your decision-making capacity. In this world, governments do not seize liberty; people surrender it voluntarily – a ‘Brave New World’ where people love their servitude, a painless concentration camp in which, as Huxley wrote, people “in fact have their liberties taken away from them but will rather enjoy it.”

This undermines one of liberty’s strongest safeguards: community. As government replaces community, people lose the habit of solving local problems themselves and they begin to surrender their agency, expecting the state to act in their place. Eventually, they reach the condition in which, as Tocqueville wrote, “they can do almost nothing by themselves.” If citizens forget the art of cooperating with one another, of pursuing common goals and solving their own problems, Tocqueville warned that “civilisation itself would be in peril.” Citizens grow weaker, more dependent and less capable. This is not the result of brute force, but of their own choice to substitute state power for individual autonomy, community and responsibility. They give up their freedom and allow others to choose for them, lulled by the illusion that life will be easier.

At its core, the loss of freedom is psychological. It is rooted in the failure to act, the failure to exercise personal autonomy, the failure to participate in community and the constant deferral of responsibility in the hope that someone else will solve our problems. The result, Tocqueville feared, would be “an insupportable tyranny even without wishing to.” A tyranny no one wanted, yet to which everyone contributed, step by step. Freedom is lost in the same manner Hemingway’s banker went bankrupt: gradually, then suddenly.

You must be logged in to post a comment.