Argentina’s poverty rate fell sharply in the second half of 2024, according to official data released this week, marking a major milestone for President Javier Milei’s sweeping economic reforms.

According to the country’s official statistics agency, the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INDEC), the poverty rate fell to 38.1 percent between July 2024 and December 2024—down nearly 15 percentage points from the first half of the year. Household poverty also declined by 13.9 percentage points, hitting 28.6 percent. And extreme poverty was cut by more than half, falling from 18.1 percent to 8.2 percent.

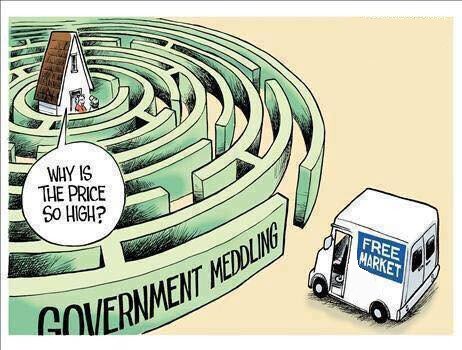

It’s a major turnaround from the beginning of Milei’s presidency. When he took office in December 2023, he inherited a poverty rate of 41.7 percent, which quickly surged to 53 percent as his administration launched a “shock therapy” program to end Argentina’s economic misery.

One of the biggest drivers behind the poverty decline is the sharp drop in inflation. Annual inflation, which reached 276.2 percent a year ago—one of the highest in the world—dropped to 66.9 percent last month. Monthly inflation has also dropped, from 25.5 percent in December to just 2.4 percent in March.

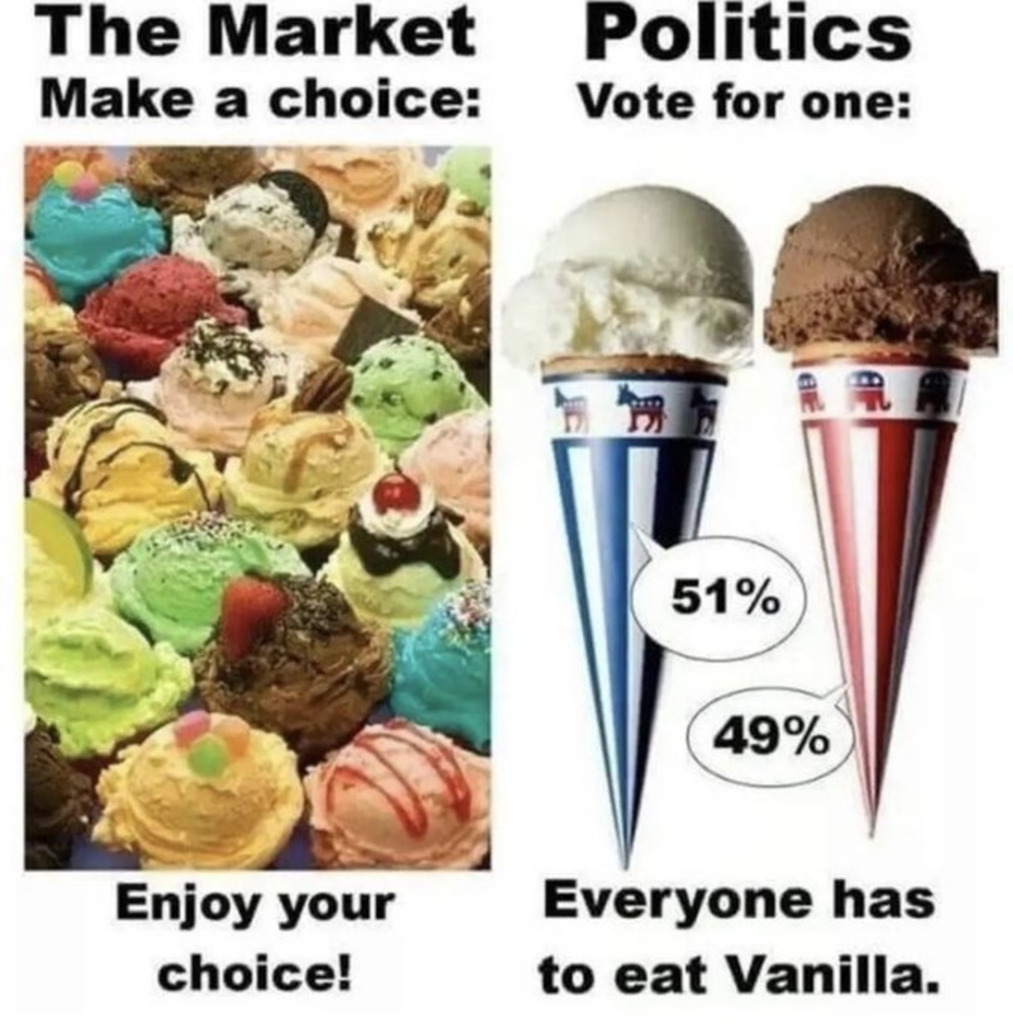

“These figures reflect the failure of past policies, which plunged millions of Argentines into precarious conditions while promoting the idea of helping the poor, even as poverty continued to increase,” Milei’s office said in a statement following the release of the INDEC report. “The current administration has shown that the path of economic freedom and fiscal responsibility is the way to reduce poverty in the long term.”

In other words, Milei’s bet on free market reforms is starting to pay off.

It’s worth remembering the situation he walked into. “Milei inherited a country suffering from more than 200% inflation in 2023, 40% poverty, a fiscal and quasi-fiscal deficit of 15% of GDP, a huge and growing public debt, a bankrupt central bank, and a shrinking economy,” writes Ian Vásquez of the Cato Institute.

In response, Milei promised a radical shift in Argentina’s economic model. His government slashed government spending, eliminated price controls, devalued the peso, cut subsidies, suspended public works, and laid off thousands of government workers. The changes weren’t popular, but they were necessary. And now, the numbers are catching up.

The economy is growing again. Gross domestic product grew in the last two quarters. The gap between the black-market dollar and the official rate has narrowed. Rents have fallen and the housing supply has increased since rent control laws were scrapped. Meanwhile, investor interest in Argentina is beginning to return, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is in talks with Milei’s government over a new program. The IMF projects a 5 percent growth for Argentina in 2025.

Still, challenges remain. Despite the improvement, over 11 million Argentines are still living in poverty, with 2.5 million facing extreme poverty. And more than half of all children ages 14 and under in Argentina are poor.

Keep reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.