So eloquent and elegant, tho…

The Air Force’s clandestine flight test center deep inside the Nevada Test and Training Range, known as Area 51 or Groom Lake, among more colorful nicknames, continues to grow as it approaches its seventh decade of operations. Constant construction has grown the remote facility dramatically since the turn of the millennium, including the addition of a massive and still mysterious hangar built at the base’s remote southern end. Now, an even larger extension to an existing hangar facility that is quite peculiar in nature points to the very real possibility that the age of large swarms of unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs) has finally arrived.

From self-driving cars, to digital assistants, artificial intelligence (AI) is fast becoming an integral technology in our lives today. But this same technology that can help to make our day-to-day life easier is also being incorporated into weapons for use in combat situations.

Weaponised AI features heavily in the security strategies of the US, China and Russia. And some existing weapons systems already include autonomous capabilities based on AI, developing weaponised AI further means machines could potentially make decisions to harm and kill people based on their programming, without human intervention.

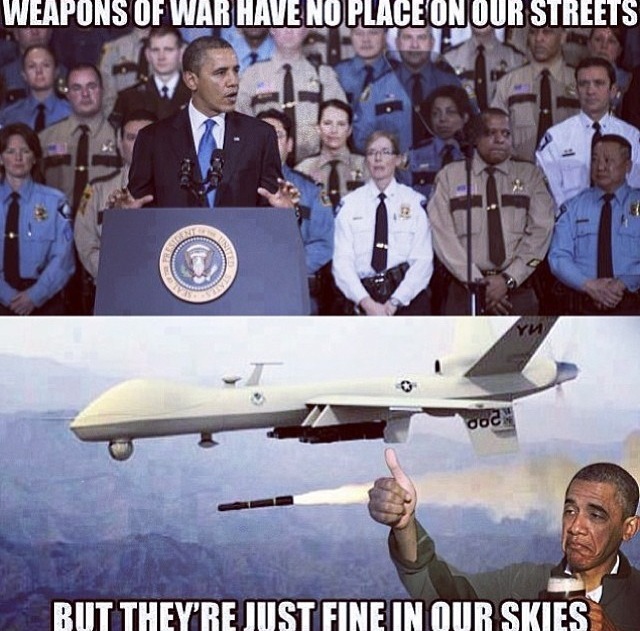

Countries that back the use of AI weapons claim it allows them to respond to emerging threats at greater than human speed. They also say it reduces the risk to military personnel and increases the ability to hit targets with greater precision. But outsourcing use-of-force decisions to machines violates human dignity. And it’s also incompatible with international law which requires human judgement in context.

Indeed, the role that humans should play in use of force decisions has been an increased area of focus in many United Nations (UN) meetings. And at a recent UN meeting, states agreed that it’s unacceptable on ethical and legal grounds to delegate use-of-force decisions to machines – “without any human control whatsoever”.

But while this may sound like good news, there continues to be major differences in how states define “human control”.

Gorgon Stare will be looking at a whole city, so there will be no way for the adversary to know what we’re looking at, and we can see everything. That same persistent eye in the sky may soon be deployed over U.S. cities.

At the time he made that comment about surveillance drones over Afghanistan, Maj. General James Poss was the Air Force’s top intelligence officer. He was preparing to leave the Pentagon, and move over to the Federal Aviation Administration. His job was to begin executing the plan to allow those same surveillance drones to fly over American cities.

This plan was ordered by Congress in the 2010 National Defense Authorization Act. It directed the Departments of Defense and Transportation to “develop a plan for providing expanded access to the national airspace for unmanned aircraft systems of the Department of Defense.” Gen. Poss was one of nearly two dozen ex-military officers who, starting in 2010, were put into positions at the FAA to oversee drone integration research. With little public scrutiny, the plan has been moving forward ever since.

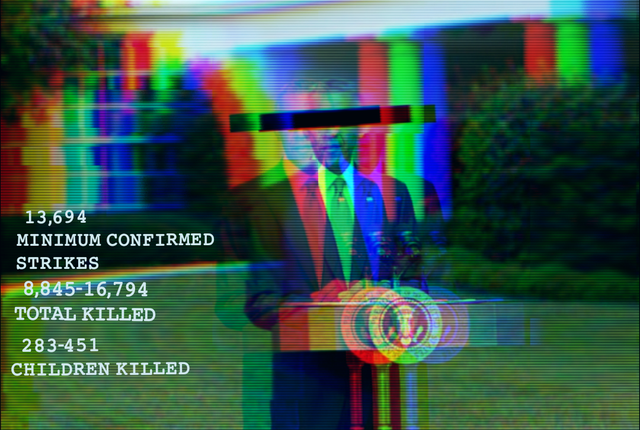

If you’re thinking that this is a partisan issue, think again. This plan has been enacted and expanded under Presidents and Congresses of both parties. If you’re uncomfortable with a President Biden having the ability to track the movements of every Tea Party or Q-Anon supporter, you should be. Just as we should all be concerned about a President Trump tracking…well, everybody else.

You must be logged in to post a comment.